Mikuláš Peksa:

The new European Public Prosecutor Office (EPPO) has been running for slightly over 100 days. The Office combating corruption and fraud related to EU funds has been celebrating achievements since the first day. Yet, it could work even better.

In the first 100 days since its launch, the Office registered up to 1,700 new crime reports and initiated over 300 investigations amounting to 4.5 billion euros in damage to the EU’s budget. Twelve cases are under investigation for the Czech Republic, including Andrej Babiš’s infamous conflict of interests.

The new anti-corruption Office, which the Pirates and I have always supported, has been going at full speed, with no plans to slow down. The new body is also an essential and revolutionary reinforcement for the EU’s existing anti-corruption institutions! The EPPO can investigate and prosecute fraud related to the EU’s funds completely independently on national court systems. Therefore, major fraudsters can no longer comfortably and arrogantly hide behind slow or biased court systems; they are held accountable by the EU directly.

Despite all this, the Office still has many flaws that need to be rectified. At the moment, it only has 120 staffers, and the Commission has been setting pointless limits on its recruitment. Some countries, such as Poland and Hungary, are not even involved in the Office’s functioning, while Slovenia is a member but has been boycotting the appointment of their own prosecutors. If the EPPO is to really and efficiently guard the EU’s budget, we need to tackle these issues.

The revolutionary institution has results

The point of the role of the European Public Prosecutor Office is to investigate and prosecute criminal offences which damage or threaten the EU’s financial interests. It focuses on problems such as corruption, money laundering, misuse of European funds or subsidy and cross-border VAT fraud. It complements the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF), which only investigates administrative fraud, while the EPPO focuses on criminal fraud. OLAF can also only issue recommendations to the Member States based on its results, but it cannot prosecute the offences it reveals.

The EPPO’s independently elected team of up to 140 prosecutors from all the involved states, led by the legendary Romanian prosecutor Laura Kövesi aims to limit the embezzlement of European funds, which currently amounts to around 50 billion euros per year.

We don’t have to go far to look at the results of the EPPO’s work. For example, in Croatia, the Office launched an investigation concerning the mayor of the Nova Gradiška municipality, who manipulated a public tender favouring his acquaintance in return for bribes. This gave the acquaintance access to up to half a million euros from the EU’s Cohesion Fund. In Italy, the EPPO tasked the police with seizing assets amounting to over 11 million euros from two companies, which used the Covid-19 pandemic to smuggle medical equipment and put people’s lives at risk.

Danger for Andrej Babiš?

The new Office can also play a massive role in the long-running scandals concerning our likely soon to be former Prime Minister Andrej Babiš. The EPPO took over the case of Andrej Babiš’s conflict of interests right at the start as one of its first investigations, 12 days after its launch at the beginning of June this year. So far, the case was being investigated by the High Public Prosecutor’s Office in Prague.

This might spell a vast problem for Andrej Babiš’s future. He will likely no longer be Prime Minister, but during his term of office, he illegally used his conflict of interests to help himself to vast sums of money from the EU’s funds. As his term of office ends, the conflict of interests will likely disappear, but that will fortunately not erase the events of the last few years.

The ambitious body still has many flaws

The new Office has been facing gargantuan demands from the start – it is supposed to manage up to 3,000 cases per year. Yet, it can be expected that in order to do that and ensure the necessary quality, any institution needs enough financing and, most importantly, staff. However, that is a problem: while the Office has enough resources, it currently only has half of the needed staff.

The situation is especially vital now because the EPPO is supposed to protect the post-pandemic recovery funds amounting to 800 bn EUR. However, he needs more funding for that, and most importantly, twice as many employees. The Commission has procured more resources for the EPPO, but the Office cannot use them to recruit new staff. The Commission’s incomprehensible measure, therefore, threatens both the functioning of the new body and the EU’s vast recovery fund, which will not be sufficiently guarded.

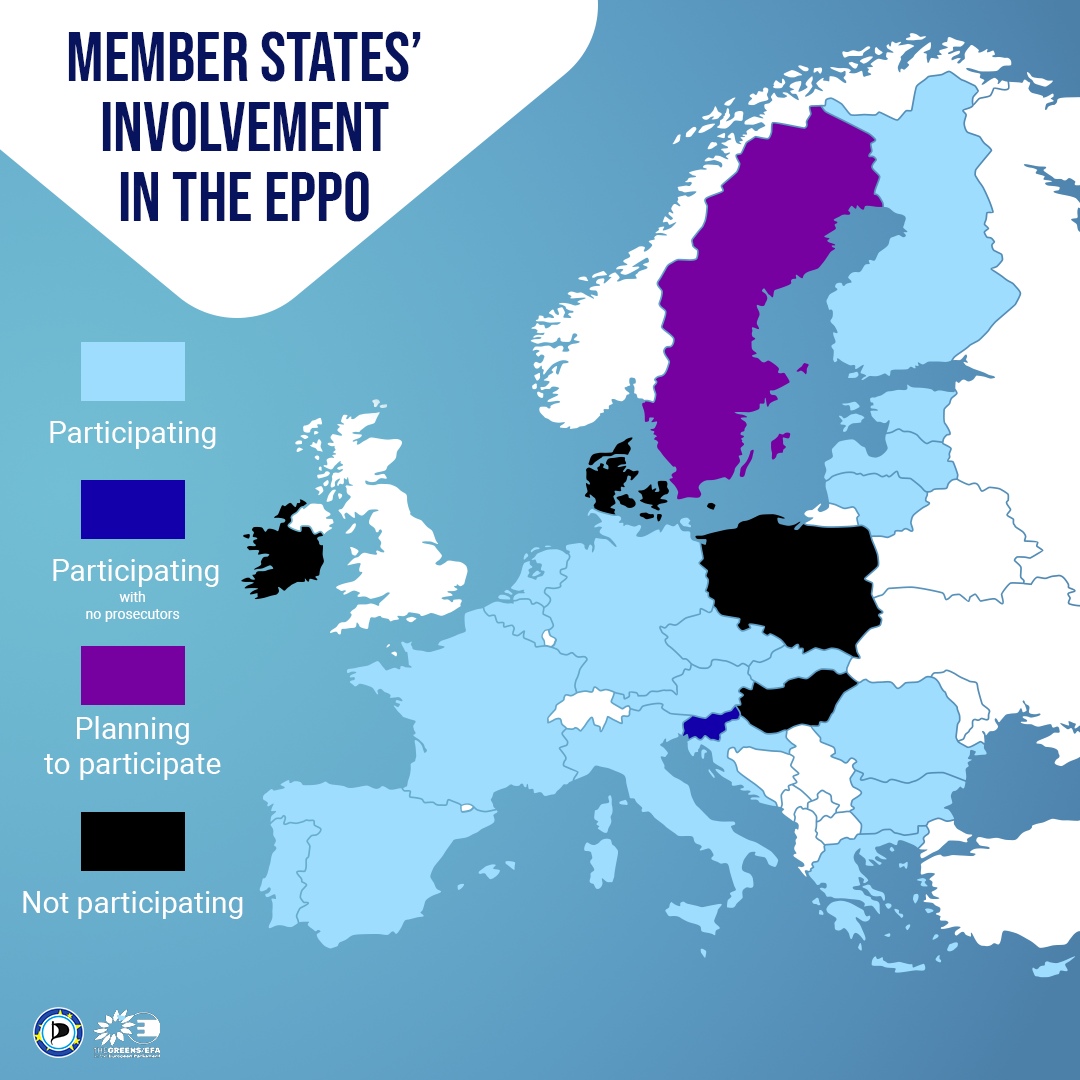

Another equally important issue with the EPPO is that only 22 out of 27 Member States are currently participating in it. Sweden is expected to join next year, but the other countries – Ireland, Denmark, Hungary, and Poland – have not considered it so far. The incomplete participation by the Member States damages public trust in the EU and European financial interests, and moreover, it complicates cross-border investigations.

For countries like Hungary, this is a grave mistake. Viktor Orbán’s Hungarian Fidesz government is infamous for controlling many Hungarian institutions, including the ministries in charge of subsidy allocation. Some subsidies, therefore, often end up in the pockets of Orbán’s friends and Hungarian oligarchs. Poland, then, is the biggest recipient of EU subsidies.

A major thorn in the side of EPPO is also Slovenia, with its government led by Janez Janša, who openly admires Viktor Orbán and Donald Trump. Slovenia did join the EPPO project, but Janša decided to postpone the appointment of two Slovenian independent delegates as European prosecutors out of a personal vendetta – in the past, they had investigated Janša himself. So far, he has been getting away with this despite protestations by the Slovenian Constitutional Court, which confirmed the vote for the delegates was perfectly fair.

Therefore, while Slovenia remains a part of the EPPO, the Office can still not identify any potential financial fraud or abuses of EU funds in the country. It will also not be able to prosecute any such offences, and that is a huge problem. Slovenia is currently chairing the presidency of the Council, meaning this also puts the rest of the EU’s budget at risk.

We cannot shoot the EPPO in the foot

We had waited long for the European Public Prosecutor Office – the first mentions date back to 1997 before the Czech Republic even entered the EU. Now that the Office is actually at work, we can see how important it is to protect European funds. We should not waste this opportunity, and the Commission must understand that the EPPO’s activities should be supported, not senselessly restricted. I think that in the few months it has been active, the Office has clearly shown that reinforcing it with 130 more staffers will be worth it.

EU funds are, most importantly, money that belongs to all Member States and their citizens. Therefore, the Commission should strive to include the remaining states and ensure that those who have joined comply with the rules. Whether the Member States are net payers or recipients, it is in our shared interest to ensure that the taxpayers’ money is used the right way, not to line the pockets of thieves and oligarchs.

0 comments on “A new EU body helps combat fraud. What has worked well and what hasn’t?”