In July 2021, the European Commission’s proposal to allow general and indiscriminate scanning of users’ private messages and photos (Chat control) was adopted by the European Parliament.

The law was presented as a temporary derogation to the EU’s privacy rules, which would allow — not force — messaging providers to scan messages. However, following Parliament’s vote, the European Commission wasted no time in preparing Chat control 2.0, a proposal that would make the general and indiscriminate scanning of our photos and messages obligatory.

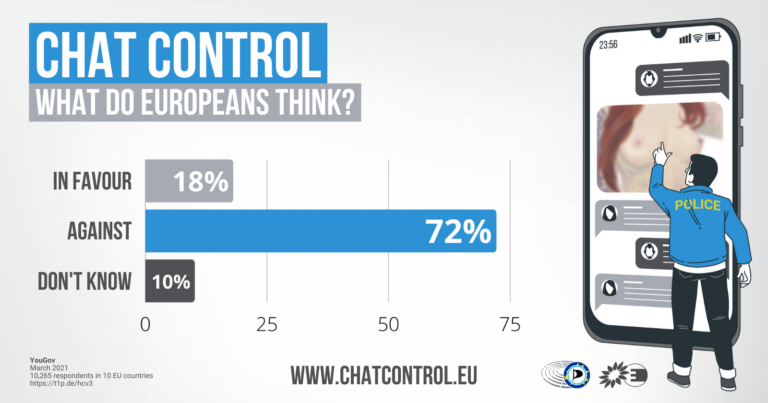

The idea has already received enthusiastic support from many EU interior ministers, but it did not get such a good reception from citizens or MEPs. A great majority of EU citizens (72%) oppose blanket messaging and chat control, according to an opinion poll conducted by YouGov among 10,265 citizens from 10 EU countries.

Despite overwhelmingly negative feedback in a public consultation, as well as a letter from MEPs expressing serious reservations about the proposal, the Commission has pressed ahead.

This bullish approach is nothing new: they rushed Chat control 1.0 through without even consulting citizens, businesses or NGOs. They did not ask citizens if they wanted chat control, and they did not ask NGOs if it will actually help address the problem it was created to fix.

A nightmare for our privacy

While Chat control 1.0 has already the potential to de facto end privacy of correspondence in the European Union, it is implemented by US providers such as Meta, Google and Microsoft only. Chat control 2.0 takes things a step further by mandating general and indiscriminate surveillance of all our conversations, using any service provider. The Commission does not say how providers should implement the screening, especially considering many messaging apps now use end-to-end encryption, meaning it is impossible for messaging providers to read our messages, but the few ideas that have been floated so far have far-reaching implications for our privacy.

Breaking Encryption

One proposal popular among some member states, is to break end-to-end encryption in the European Union, either by forcing providers to store copies of the encryption keys of users, or by using a “master key” for EU customers which will allow decryption of conversations.

These proposals pave the way for abuse by authorities in member states, for example, by scanning for content beyond the limits set by the regulation, or by developing mass-surveillance of encrypted communications. Even if the proposal were to contain limits on what uses of these keys are acceptable, it would be impossible to guarantee that these limits are being respected, especially considering the existing difficulties enforcing the rule of law in the EU, the fact that the Commission has no competence with regards to national security, and the fact that previous mass-surveillance programmes have evaded oversight.

Worse still, if foreign governments or hackers got a hold of keys, they could effectively spy on all EU citizens, including lawmakers, journalists, psychologists and doctors, activists and regular citzens who rely on end-to-end encryption to protect their conversations.

Using AI to look for “unknown” material

Another approach the Commission are exploring is using error-prone AI to search for illegal content. Here, the Commission has fallen into the trap of believing AI is a “magic bullet” that can solve any problem. It is not.

Artificial Intelligence looks for patterns, but has no understanding of context, meaning a plathora of messages, from holiday photos to sexts, will be incorrectly flagged. Worse still, AI’s frequently have issues correctly identifying the age of individuals in photos, especially when those individuals are from minority groups (ethnic minorities, LGBTQI, persons with disabilities).

As a result, images or conversations flagged by AI require human verification, meaning your intimate and personal photos or videos may end up in the hands of global staff or contractors where they are not safe. If you look younger than you are, or if you belong to one of these groups, private conversations, and even your nudes are likely to end up in the hands of law enforcement. To make matters worse, there are plenty of examples of law enforcement and intelligence agencies copying or sharing nude photos they obtained as part of investigations with their colleagues and third parties.

Client-side scanning with Hashes

Experts suggest to turn our mobile phone into a surveillance device: Before encrypting and sending a message your phone would search photos and videos for matches with blacklisted material. If the algorithm reports a hit, your private message, photo and/or video would be automatically reported and disclosed to the provider and/or police.

According to the Swiss Federal Police 86% of reports of blacklisted material are not criminally relevant. The non-transparent database of blacklisted material contains vast amounts of photos and videos that are not criminally relevant (e.g. children playing at the beach) and will still get you reported to the police for alleged “child pornography”. Even if you are innocent the investigation can result in questioning, house searches, confiscation. Also a large share of investigations target minors – the children this is intended to protect.

Most importantly such on-device surveillance would undermine trust in the privacy and security of sensitive communications, disrupting activities e.g. of whistleblowers, human rights defenders, pro-democracy activists, journalists in many countries. Experts warn that once our mobile phones have been turned into bugs it is only a small step to expand the system to alleged copyright violations, terrorism, or political dissent. Such backdoors can also be used by governments to surreptitiously intercept the content of sensitive correspondence which is believed to be securely end-to-end encrypted.

Ineffective and counterproductive?

There are also a wider set of issues that make Chat control 2.0 counterproductive:

Firstly, authorities would have to focus their limited resources on dealing with cases flagged by the system, which would likely include an avalanche of false positives. They will have even less time to investigate abuse cases.

Worse still, the law would also make it harder to catch and prosecute sex offenders. This proposal would push even more criminals on to the darknet, on websites that are hidden and untraceable, making it impossible to catch co-conspirators.

A slippery slope?

While Chat control 1.0 already puts us on a dangerous path, Chat control 2.0 puts us on a slippery slope: Simply giving governments the possibility to scan our conversations and photos, even on a limited scale, would openly invite abuse: once governments have the technical means to scan messages as part of EU law, they can expand scanning through national law under the guise of “National Security”, an area in which the European Union has no powers.

Such an expansion could target ‘terrorist content’, which might seem reasonable until you realise that some governments classify organisations such as greenpeace or extinction rebelion as potential terrorist groups, effectively giving them the authority and means to watch protest groups and NGOs.

What can we do ?

While the backlash over Apple’s photo scanning proposal did force the Commission to delay the legislation, they have now announced that it will be tabled in March 2022. Despite Germany’s new government now opposing chat control the proposal is still highly popular among other member states, and the European Parliament’s position remains uncertain, which is why it is vital we campaign to stop it!

On our homepage chatcontrol.eu we invite you to contact the responsible Commissioners.

0 comments on “Chat control 2.0: the sequel nobody asked for”