Donald Trump banned TikTok and WeChat in the USA from the middle of September onwards, in a short-sighted escalation of his conflict with Beijing.

Nevertheless, the risk posed by Chinese software corporations is real, not only when it comes to user privacy. Chinese algorithms are on the verge of censorship and Chinese companies are as enamoured with forming huge monopolies as their American competitors.

Europe is now standing at a crossroads. We should not get involved in the war between China and the USA at all. Instead, we can use the newly vacated space for writing our own rules and creating a market environment dedicated to protecting user privacy and capable of leveraging the power of a truly free market.

What is the problem with Chinese corporations?

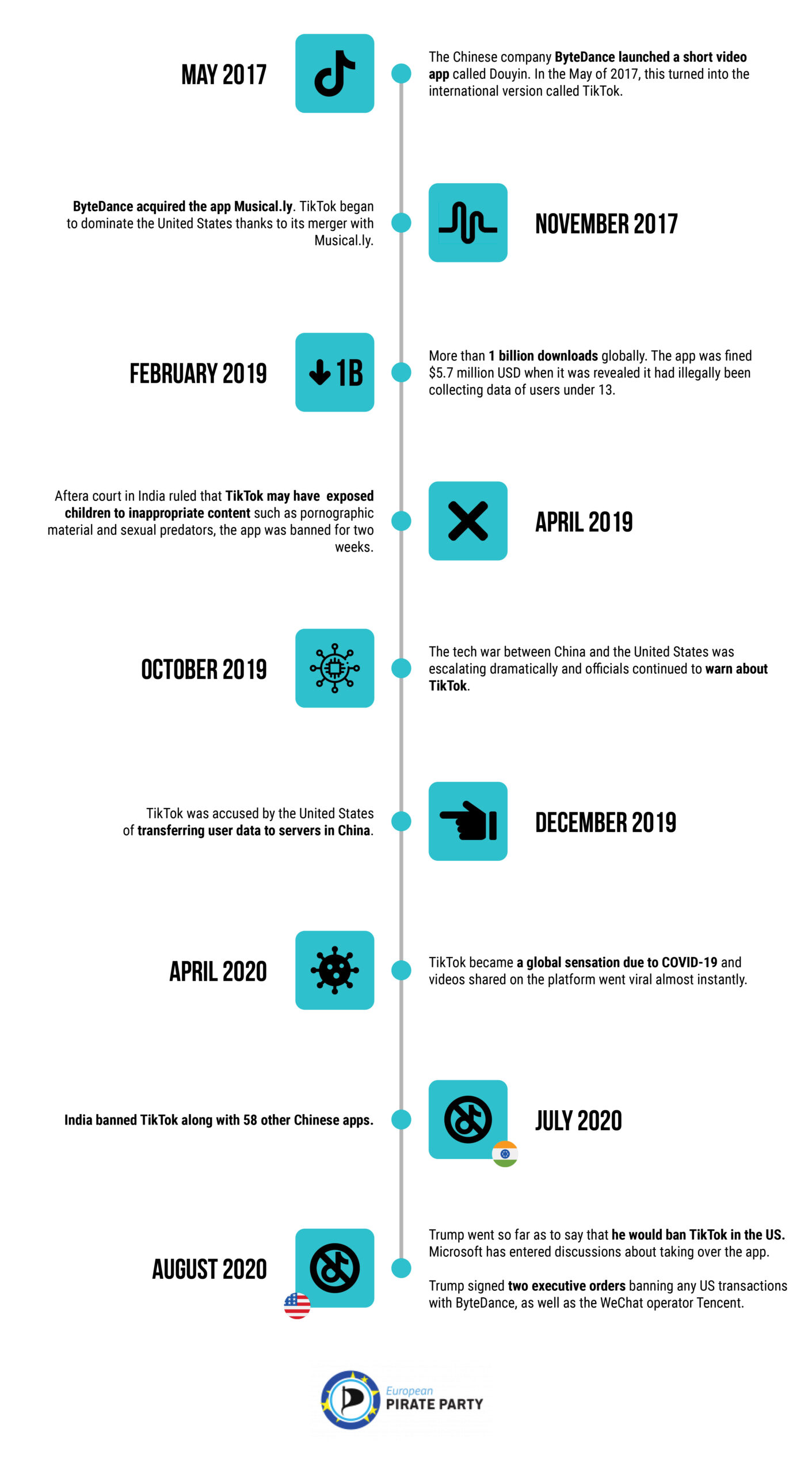

Chinese legislation dictates that corporations in China, meaning also TikTok, are automatically required to collaborate with the Communist government, which includes handing over user data. And TikTok has been amassing a huge load of data; it has already been fined for violating American laws by collecting the data of its child users. The Wall Street Journal also revealed that TikTok had been collecting MAC addresses identifying individual users for 18 months, even though the tactic had been banned by Google. Even the fact that TikTok stores user passwords is dangerous, as most users sadly use the same password for multiple apps.

Obviously, feeding astronomical volumes of personal data to any digital corporation is never a good idea, whether we’re talking about Facebook, Google, or any others. However, sending data to both large corporations and the Chinese government is the worst possible combination.

TikTok is also facing censorship allegations, which are no less serious. What you see on the homepage is determined by algorithms and the corporation’s employees. In one instance, TikTok blocked the account of Feroza Aziz, an activist, for her brilliant video criticising the Uyghur cultural genocide. In this case, TikTok quickly apologized and chalked the incident up to a “human moderation error”, since their human moderator probably failed to notice that standards for freedom of expression are set slightly higher in the West than in China. Similarly, TikTok has shown a suspiciously small number of videos from the recent protests in Hongkong, and videos on Tibet seem to be just as “unpopular”.

ByteDance, TikTok’s parent company, has rejected all the allegations. It claimed that the data of European and American users was stored on servers outside of mainland China. ByteDance also wants to create a “transparency centre” in Los Angeles, with independent experts monitoring their algorithms and content policies. Yet this is where we get to the crux of the matter: these measures might suffice if TikTok was making cars or another physical product. Instead, its product is an extremely complicated piece of software, and finding any kind of backdoors in that is far from easy. Facebook’s former Chief Security Officer, Alex Stamos, confirmed this for The Economist: As long as Beijing-based engineers have access to data stored outside of China, their government could force them to hand it over.

So why not ban TikTok and similar services?

Trump’s decision is full of holes.

The first one is clarity: Trump’s order was to enter into force 45 days after it had been issued (which would mean the middle of September), banning all “transactions” between American citizens and companies and TikTok and WeChat. His order also charged the Department of Commerce with specifying these “transactions” within 45 days.

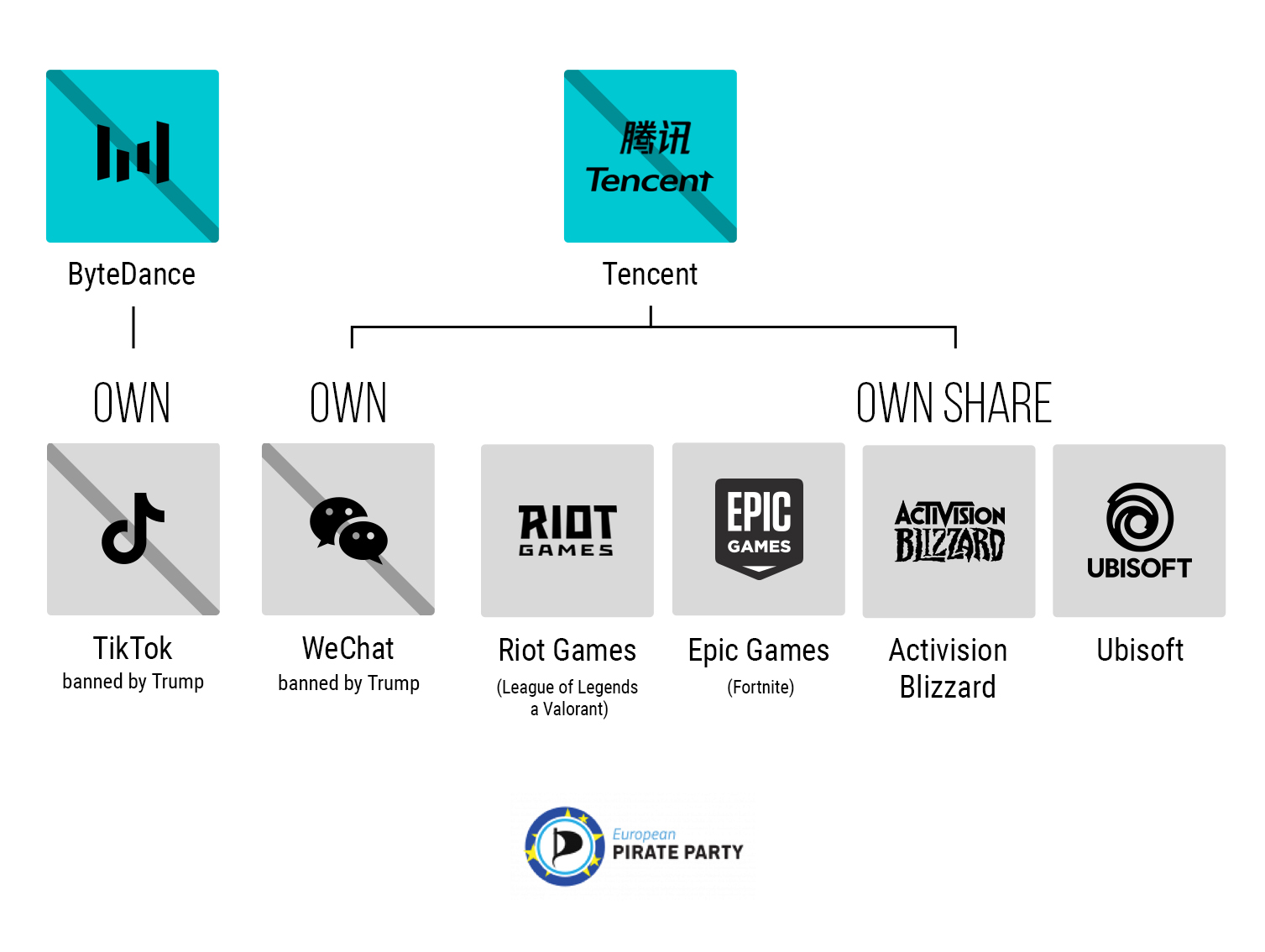

The question is who would be impacted by this ban. At first, Trump’s decision caused panic amongst fans of popular games such as Fortnite and League of Legends. The White House quickly tried to dispel these concerns by explaining that banning these games was not their goal. When it comes to big platforms, it can easily be the side effect, though. In recent days, big players such as Epic Games, Apple, and Google have also entered into a game of tug-of-war, but I am planning to cover the struggles between game platforms and the way they work with your data in a separate article.

It is almost certain that Google and Apple will have to remove these apps from their American online stores. But how will they make sure that users don’t try to circumvent the official routes? What will the 100 million Americans who have already installed TikTok on their devices do? Does the ban apply to Google and Apple services in China? And how about Europe?

The next problem is the real purpose of such a strong state intervention. Trump is not doing this to protect his citizens from data misuse or the massive monopolies strengthened by these practices. His goal is to exert as much pressure as possible on TikTok, in order to force it to separate its activities in the US and sell them to Microsoft. Microsoft might be somewhat less problematic than ByteDance but feeding one of the most powerful giants of the Internet industry, which is not particularly concerned about your privacy either, is a highway straight to hell. It means no real improvement for users: their data will simply belong to a different large brand. In the meantime, Trump has already openly asked for his share of the spoils.

The third problem is the effect this will have on customers. WeChat belongs to TenCent, one of the biggest players in the video gaming industry. It is therefore no wonder, that right after the order was issued, people started asking whether the ban would also apply to the popular League of Legends. The government has since stated that the ban would not affect these games, but the text of the executive order does not specify this.

The last problem is legal certainty. Right after Trump issued the orders, the stock market reacted quite dramatically, but in the long run, it is not even certain the ban will enter into force: ByteDance has already said they would go to court over the case. Trump’s orders were overturned by courts once before, in the case of the Muslim Ban. I am convinced that a healthy business environment is determined by its predictability and fairness. A state willing to randomly pressure one foreign corporation into selling some of its business to another national giant is definitely not a shining beacon of freedom.

Another blow for the world wide web

Trump’s ban will cause practical problems for Chinese and American corporations and users alike, but it has one other aspect: It represents another step in a sort of deglobalization of the virtual world (amongst other things). Vint Cerf, one of the founders of the Internet, has warned against creating a “fractured Splinternet”.

There is no doubt that this trend started in China. The Chinese government’s restrictive Internet policy is often aptly labelled the Great Firewall of China. After all, WeChat owes its popularity to the fact that Google and Facebook have been banned in China. We should all be pushing for the Great Firewall to be dismantled and torn down, but instead, Trump has started building a little wall of his own. That is a major strategic error by the USA, and we could all pay for it. The global Internet and globalized communication bring their own set of challenges, but their benefits are undeniable. Freedom of information has brought us endless waves of entertainment, as well as the opportunity to make better decisions. It connects us all. A world in which the Chinese only have access to Chinese information and Americans only to the American ones is a world that is much less likely to go forward; and one that I would hate to live in.

How can we face this threat?

That’s the million-dollar question.

The American way of unbridled freedom and systemic benefits for the biggest players led to a market dominated by huge corporations and dwindling competition.

I am convinced that the key is a truly competitive market. Such a market needs fair rules and good regulation to protect users’ rights and privacy and avoid the rise of large monopolies.

The USA has a long way to go in this. Their anti-trust legislation used to be a shining example for the rest of the world, but in the last two decades, they have been lagging behind. They also sorely lack any legislation similar to the EU’s GDPR, as civil society and recently also The Economist have been saying. Yet instead of devising a systemic solution, the USA has chosen to engage in reckless and short-sighted attacks on individual corporations.

After all, the way EU countries promote competition has earned them high ratings in the last Digital Quality of Life Index when it comes to accessibility: competition between a number of Internet providers is much better for consumers than the American system of Internet giants. And when it comes to e-security, EU member states have been crushing all other countries thanks to GDPR.

Being better than others doesn’t mean we can rest easy, though. Quite on the contrary. The EU might be on the right path in some things, but there’s still a lot of fine-tuning to do. For example, in GDPR. The legislation explicitly forbids data transfers to foreign powers, but enforcing this rule is a problem. It is left to national authorities and there is no centralized control body. As a result, there has not been a single relevant case of a company handing over data to a third country government and getting fined for it. TikTok’s security hub, for example, is stationed in Ireland, where the national regulator is allegedly rather weak. Investigations also take far too long.

We need to use all of our options. We are in dire need of a centralized control body for large software corporations, as enforcing GDPR for them is much harder than for e-shops, for instance. We also have to pressure China to change its laws that force Chinese corporations to collaborate with the government. And when we’re at it, our American allies’ track record in this issue is also less than stellar. After all, we should be able to say what we don’t like to our allies, right?

Regulating software corporations is definitely going to be a long process with an uncertain result. It’s no different from hackers who are always one step ahead, forcing security companies to merely reacts to existing threats. Companies like TikTok will also always pose a risk of having a backdoor to personal data or a censorship mechanism in their algorithms.

We cannot play this game forever. Europe should not get involved in the war between China and the USA at all. Instead, we can use the space to write our own rules and create a market environment dedicated to protecting user privacy and capable of leveraging the power of a truly free market.

0 comments on “Europe cannot get involved in the war against TikTok; we have to start making our own rules”