Mikuláš Peksa:

The ties between Russian energy companies and European politicians have been powerful.

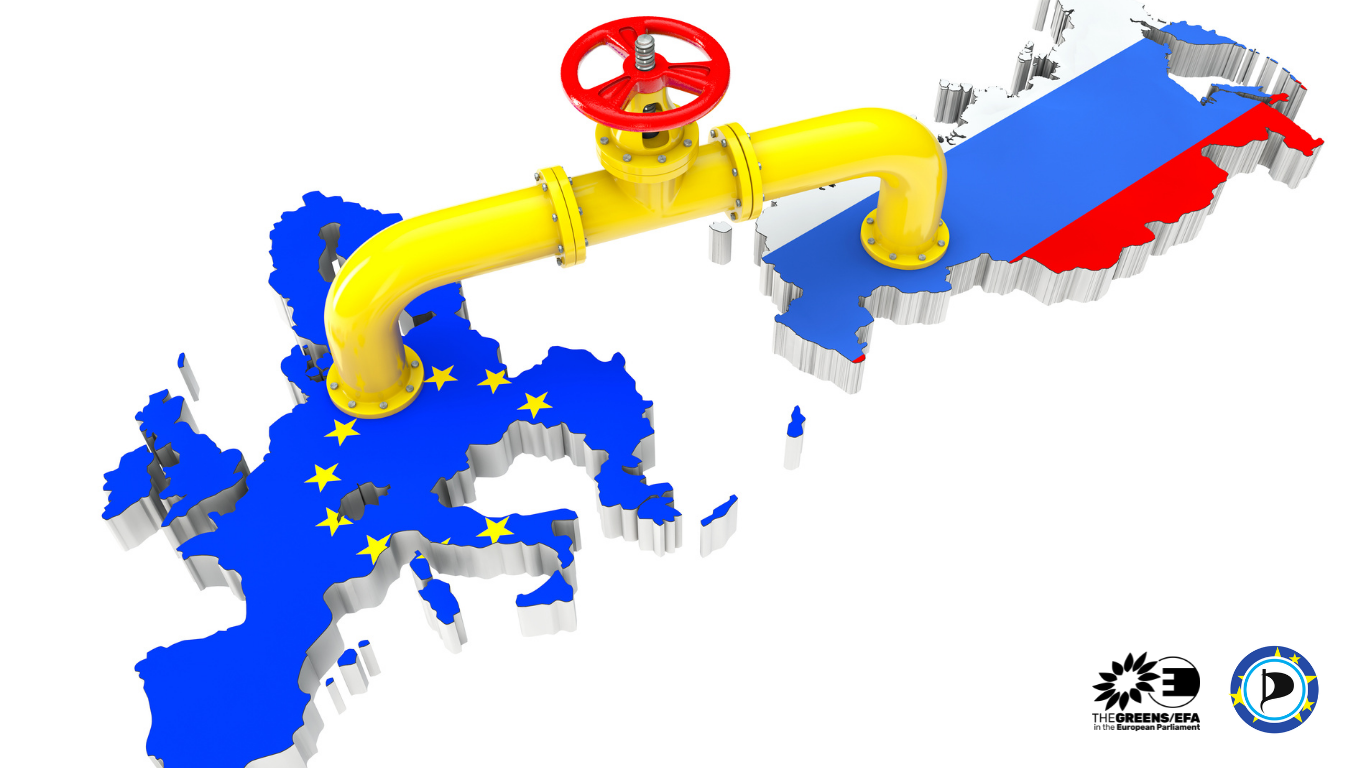

Europe’s dependency on Russian fossil fuels has proven to be a huge problem, especially recently. At the moment, around 40 % of the EU’s annual gas consumption comes from Russia. While Germany owed “only” two-thirds of its gas to Russia last year, states like Bulgaria and Hungary used Russian gas to cover over three-quarters of their total gas consumption.

The debate on lowering Europe’s dependence on Russian gas has been going on at least since 2009. At that time, under the last Czech presidency, Russia closed the taps on the gas pipelines going through Ukraine for two weeks. The discussion gained a second wind after Russia annexed Crimea.

Nevertheless, EU member states kept becoming even more dependent on Russian gas and energy. While there are many reasons behind this, one of them is easy to define: Russian energy companies have been successful at lobbying, using high-ranking European politicians and civil servants as intermediaries.

A slightly different revolving door

Perhaps you have heard the term “revolving door”. It refers to a nasty phenomenon which has been around for a long time in many European countries. I have even written several articles about it, proposing a solution that might efficiently curtail this practice, at least in EU institutions.

But what is this revolving door, really? In practice, it means that someone who used to work in the public sector (for example, as a high-ranking elected politician or civil servant) transitions to the private sector after the end of their public sector career. It can, of course, also go the other way around, but the former tends to be much more dangerous.

Why is it a problem? High-ranking politicians and civil servants naturally have the right to find another job. However, some of them exploit their contacts and knowledge of internal documents from their previous function to lobby for the interests of other countries or private companies. Nobody can ensure that they will not give government secrets away.

Chancellors, ministers, and advisers

Russian energy companies such as Gazprom, Lukoil, and Rosatom use these high-ranking European politicians and civil servants to get to the forefront of EU member states’ energy policies.

The former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder is a textbook example. Under his rule, Germany signed an agreement with Russia on the Nordstream pipeline construction. After his election failure, his outgoing government still paid 1 million EUR in construction costs if Gazprom didn’t repay the loan. Shortly after he stepped down, Schröder became one of the Nord Stream AG Shareholder Committee managers and later expanded to Nord Stream 2.

Former British Conservative MP and Minister for Climate Change Greg Barker has been through the revolving doors several times. Before going into politics, he worked for the Sibneft Oil Group, owned by the oligarch Abramovich, and after leaving politics, he became Chairman of EN+, a Russian aluminium and hydroelectricity giant owned by another Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska

The list of Russian energy lobbyists also includes the right-hand man of Czech President Miloš Zeman – Martin Nejedlý. I probably don’t even need to mention Mr Nejedlý’s ties to Russia, but it might be worth noting that the President’s external advisers worked as the head of LUKOIL Aviation Czech between 2007 and 2015. He founded the company himself upon agreement with the Russian gas giant.

We can make it better

It is important to admit that revolving doors in energy are not just a Russian speciality. My Greens / EFA colleagues published a study focused on 13 member states. They identified up to 88 similar revolving door cases in the energy sector.

Europe is dangerously dependent on Russian energy. As we can see from the current development of the war in Ukraine, that is quite a significant issue. As such, we cannot let Russia blackmail us further. We have no other choice but to get rid of our dependence on Russian gas for good.

At the beginning of March, the European Commission introduced the REPowerEU plan, which aims to cut down Europe’s dependency on Russian gas by a significant share by the end of this year and phase it out entirely by 2030. A swift transition to renewables will ensure better electricity and gas prices as well as a more secure energy supply for EU member states.

Weaning ourselves off of Russian energy will be a long process, but if we genuinely manage it, we will definitively limit attempts by Russian energy companies to manipulate the joint European energy policy.

0 comments on “Russia’s energy companies have been influencing the energy policy of European countries for a long time. How?”