Despite warnings by the European Commission and the European Anti-Fraud Office, the new Slovak Minister of Agriculture granted the Agricultural Paying Agency the power to distribute EU funds once again. However, the institution has not yet undergone the necessary anti-corruption reforms by far.

Slovakia’s long-lasting systemic corruption problems are more or less universally known at this point. For decades, the level of corruption in Slovak institutions has been so high that it would be no wonder if it towered over the Tatra mountains. The political corruption crisis Slovakia has been going through in recent years has also not helped – it has cost the country several governments, with members endowed by the strange, almost supernatural ability to turn up as suspects in anti-corruption investigations.

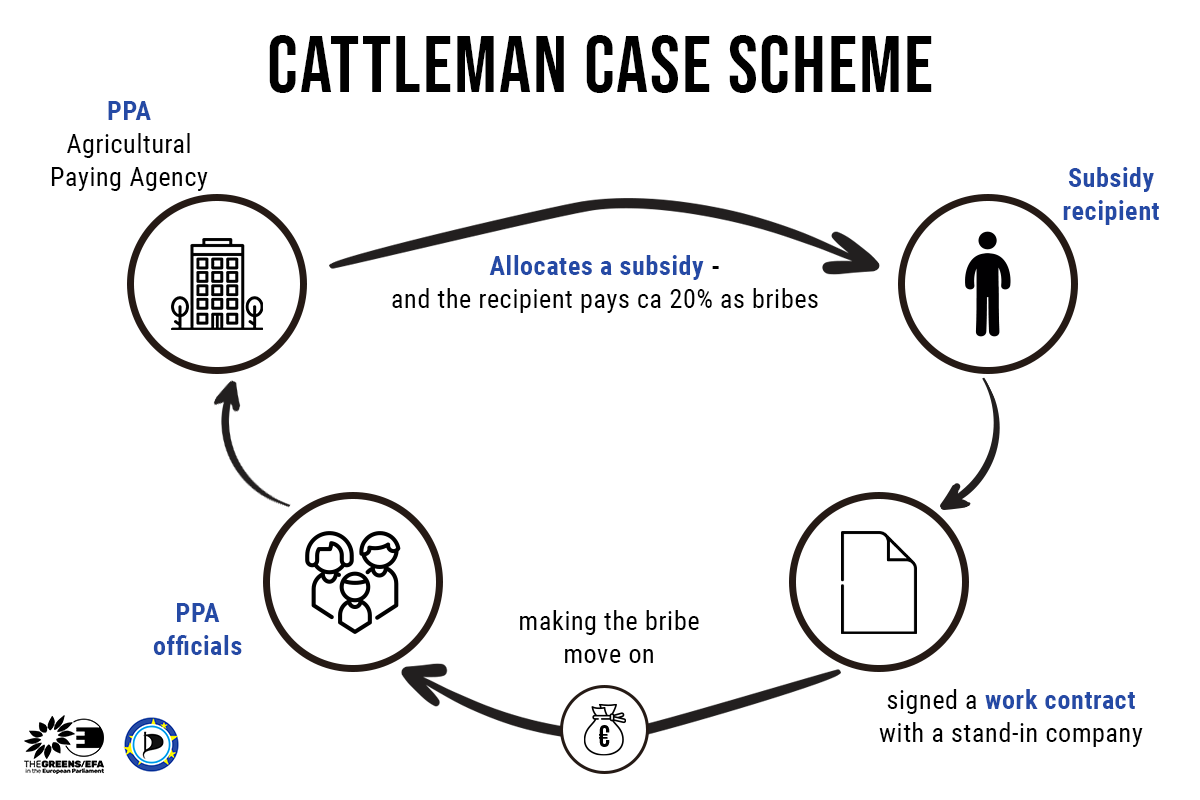

Later, the “Cattleman” corruption scandal came to light in relation to the murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak. That revealed the far-reaching corruption permeating the Slovak Agricultural Paying Agency (PPA) from head to toe. The Agency took bribes to distribute millions in euros allocated for supporting agriculture and rural development to Slovak mob bosses and oligarchs. It is no coincidence that the Agency’s Slovak nickname is the “symbol of corruption”.

Since last October, the Agricultural Paying Agency has been on probation. It was to be reformed – otherwise, up to 25 % of its payments from the Rural Development Programme would not be reimbursed. The new government claims it has managed the reform, but results seem to only exist on paper so far. The changes have failed to have an effect on the Agency itself as of yet, or they have not been implemented yet, and despite improvements, most problems persist.

If the Slovak Ministry of Agriculture wants its projects to be reimbursed from European taxpayers’ money, it needs to make sure that very money does not end up funding local mobsters and oligarchs.

Empty reforms

Many things have changed since I last wrote about Slovakia. Slovak politicians have been trying to reform the Agricultural Paying Agency after its dreary state was publicised and the Commission held up a warning finger.

Since last October, the Agency has been on one-year probation, and it was only granted a partial accreditation for allocating EU funds. If the PPA were not successfully reformed, Slovakia would be in danger of losing its accreditation altogether, as well as the only institution certified to distribute subsidies to Slovak farmers.

The new Minister of Agriculture, Samuel Vlčan, was elected only this June and took up his function in September – and he decided to postpone all existing subsidy requests so that the Ministry would not have to fill the gap in EU funds out of their own pocket.

The Commission has finally decided to address the situation in Slovakia, capping the agricultural subsidies the PPA is allowed to pay out. The huge rate of error in agricultural subsidies found in the Cattleman scandal meant the Commission would not reimburse 25 % of its subsidies to Slovakia until the state could guarantee the money would not go to oligarchs.

Since then, over 1,200 subsidy requests from farmers have stacked up in the PPA. Since the start of the summer, the Agency has held up subsidies amounting to over 60 million euros.

In order to regain its full accreditation, the Agency had to introduce 72 measures and mechanismsto prevent the embezzlement of EU funds and corruption. The new minister claims the PPA has managed that this October.

But there is a catch: a significant part of the measures have only been adopted on paper, and the Commission has refused to recognise the current state of the Agency, recommending extending the probation by 4 months.

Irregularities damage trust in agencies

We discussed the PPA irregularities on the Monday before the last with the representatives of the Commission and OLAF and Minister of Agriculture Mr Vlček at a session of the Committee on Budgetary Control (CONT), which I am a part of. We congratulated Mr Vlček on the gradual improvements in the PPA, but we also reminded him of a number of mistakes that make it impossible to grant the accreditation.

The Slovak government persists in not taking OLAF indictments seriously – it has not approved a single one out of nine total. During the OLAF mission to Slovakia, the PPA submitted important documents late, and their quality was relatively low. The Agency has also been undergoing massive staffing and management changes, complicating its collaboration with other bodies.

It is also remarkable that despite all the issues and although the Agency’s propensity for corruption is generally known, the salaries of the management have started rising mysteriously.

The Agency has taken up the Commission’s crucial anti-corruption tool, but it has not uploaded enough high-quality and understandable data to allow it to work as it is supposed to. Alongside its digitalisation, the PPA has also been cutting the number of the so-called “crossing” cases, in which multiple applicants request subsidies for the same land – but it has not done so sufficiently.

Corruption Office

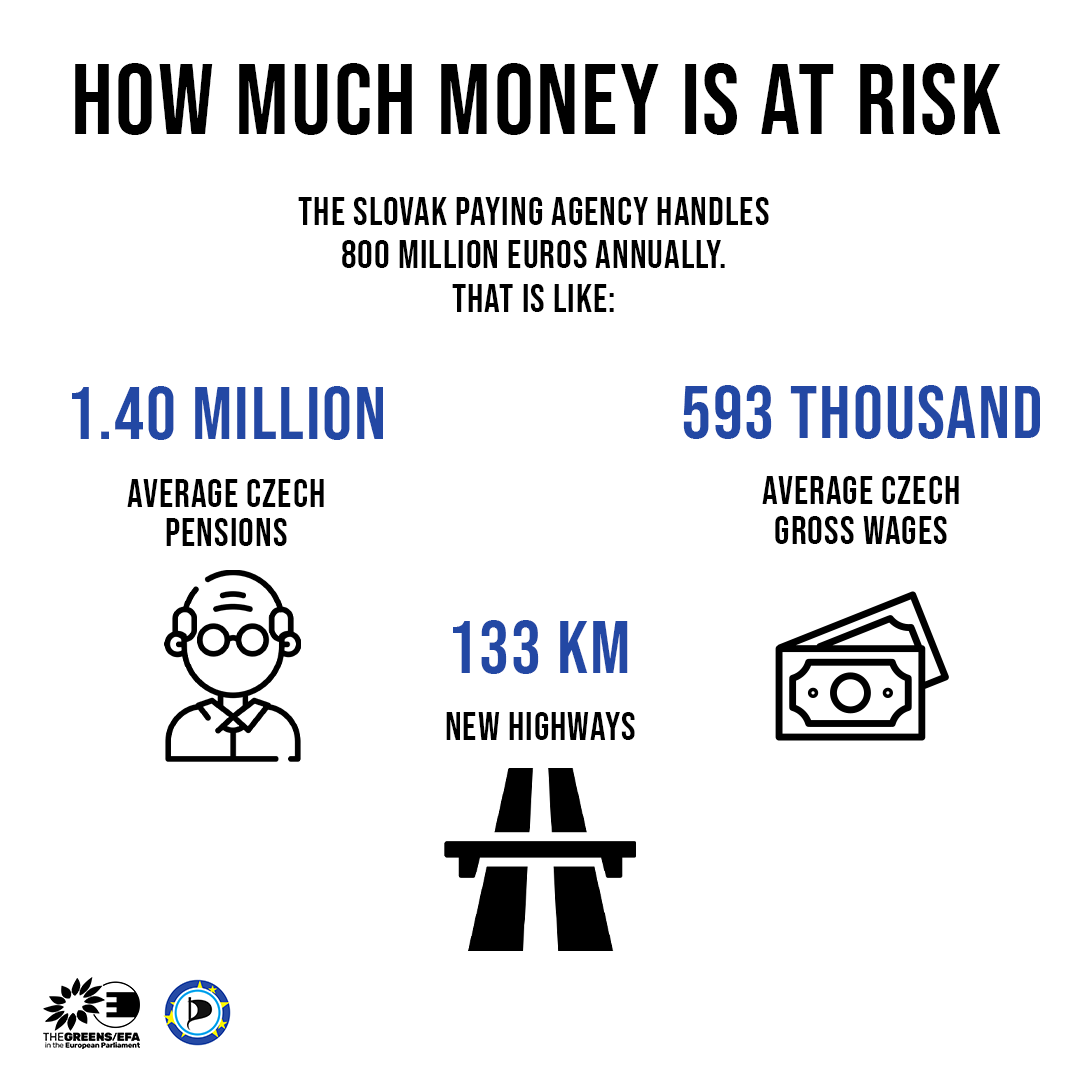

I have already written several articles on the Cattleman case on my website, reporting on its development. To summarise: the case relates to the PPA, a body responsible for allocating EU funds as part of direct subsidies to Slovak farmers. Since its foundation in 2004, it has distributed over 12 billion euros. The Agency was involved in a vast fraud scheme, with corrupt PPA civil servants taking massive bribes to allocate small farmer subsidies to the lackeys of local mob bosses and oligarchs. A recent in-depth audit in the Agency also revealed that corruption was confirmed in up to 60 % of audited cases (grant calls, public tenders etc.).

Therefore, it is absolutely essential to protect paying agencies from corruption, both in Slovakia and in all other EU Member States. These agencies are responsible for distributing ca. 80 % of the EU’s budget for individual projects. This is especially important for agencies responsible for distributing agricultural funds, which comprise a whole third of the EU’s budget – and since the Commission is unwilling to act, this year they have gained more power and flexibility over who they allocate the money to. Due to low transparency in at-risk states, such as Slovakia or the Czech Republic, there is a danger that huge sums will be lost to the mob or oligarchs.

What’s next?

I truly appreciate the efforts by Slovakia and the Minister of Agriculture to turn the Agency back into a respected institution that we will be able to trust with fairly distributing European funds to those they are meant for. However, they need to realise that if they rush the job and some of the changes only stay on paper, it will solve nothing.

Therefore, the Commission should ensure sufficient transparency in the new body and make sure any potential subsidy offences are legally enforceable. Member States should therefore be obliged to publish a machine-readable list of final beneficiaries of subsidies. Thanks to artificial intelligence, we have a chance to find up to 90 % of subsidy fraud, compared to the current 5 %. We also have the new European Public Prosecutor Office, which can investigate and prosecute corruption in the Member States when it suspects local institutions of inaction. For further suggestions on ensuring EU funds don’t line the pockets of mob bosses and oligarchs, you can read an older article of mine.

0 comments on “The Slovak “Corruption Office” is at it again. It may cost us billions of crowns”