The new Pandora Papers case uncovered the biggest financial scandal of the century. It includes Andrej Babiš and up to 100 billionaires, 300 public figures, and 40 global leaders. What can we do to prevent mass fraud and corruption by the world’s oligarchs?

On Sunday evening, the global media was shaken by a major piece of breaking news. The collaboration of over 600 investigative journalists worldwide gave birth to the so-called Pandora Papers scandal: the most extensive data leak on offshore companies in history. Several terabytes of dossiers shone a light on global leaders, Italian mobsters, and music stars who engaged in tax avoidance, tax evasion, and money laundering using shell companies in tax havens.

The Pandora Papers report includes the Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, as covered by the investigace.cz server. Apart from his massive conflict of interests, he now has a new problem. He used his offshore companies to launder, or at least not publicly declare, almost 400 million CZK. Then he bought several properties, including a luxury castle at the French Riviera close to Cannes with this money.

Where did he get the money? How many more offshore companies is Andrej Babiš hiding? How is it possible that nobody found out about it for so long?

The EU has been dedicated to tackling fraud, corruption, and money laundering for many years.

In recent years, rules on tackling money laundering have improved both on the global and the European level, and the common reporting standard on the automatic exchange of tax information has been established. However, as the latest news show, this is not enough by far.

What can we really do about it?

In short, the Pirates have been making proposals to efficiently prevent such issues in the European Parliament for several years now. Most of all, Europe needs a standardized, interoperable digital monitoring system that will allow for public oversight over how beneficiaries of public funding and politically exposed persons use their money. This system should include data on the final beneficiaries of companies and subsidiaries and be connected with up-to-date company databases.

Clear and publicly accessible data will help budgetary control authorities uncover and then prosecute specific cases of corruption or fraud. The same rules should apply for political parties – for example, in the Czech Republic, Pirates have managed to make it mandatory for parties to have transparent bank accounts. However, we can only achieve that if Member States fully cooperate with one another and with the EU institutions.

Babiš the Demagogue

Unfortunately, Andrej Babiš and conflict of interests go together like Laurel and Hardy – nobody can even imagine one without the other. Therefore, it is no surprise that Andrej Babiš, a long-standing government member, and for four years now the Prime Minister, decided to lie to his entire nation and intentionally not include all of his assets and income in his assets declaration. You would not be able to find the companies he used for his money laundering scheme in it.

Throughout his run as Minister of Finance, Andrej Babiš also focused on EU legislation on tax fraud, which he tried to block against the will of the other Member States and the Commission. Since at that time, Mr Babiš had already owned several offshore companies, he in fact has two conflicts of interests at once, not just one. A review of the European financial regulation is coming up soon, and because of cases precisely like this one, we need to make a clear stand for strengthening the conflict of interests legislation. Especially as a state that is in danger of having its EU subsidies frozen because of our Prime Minister’s conflict of interests.

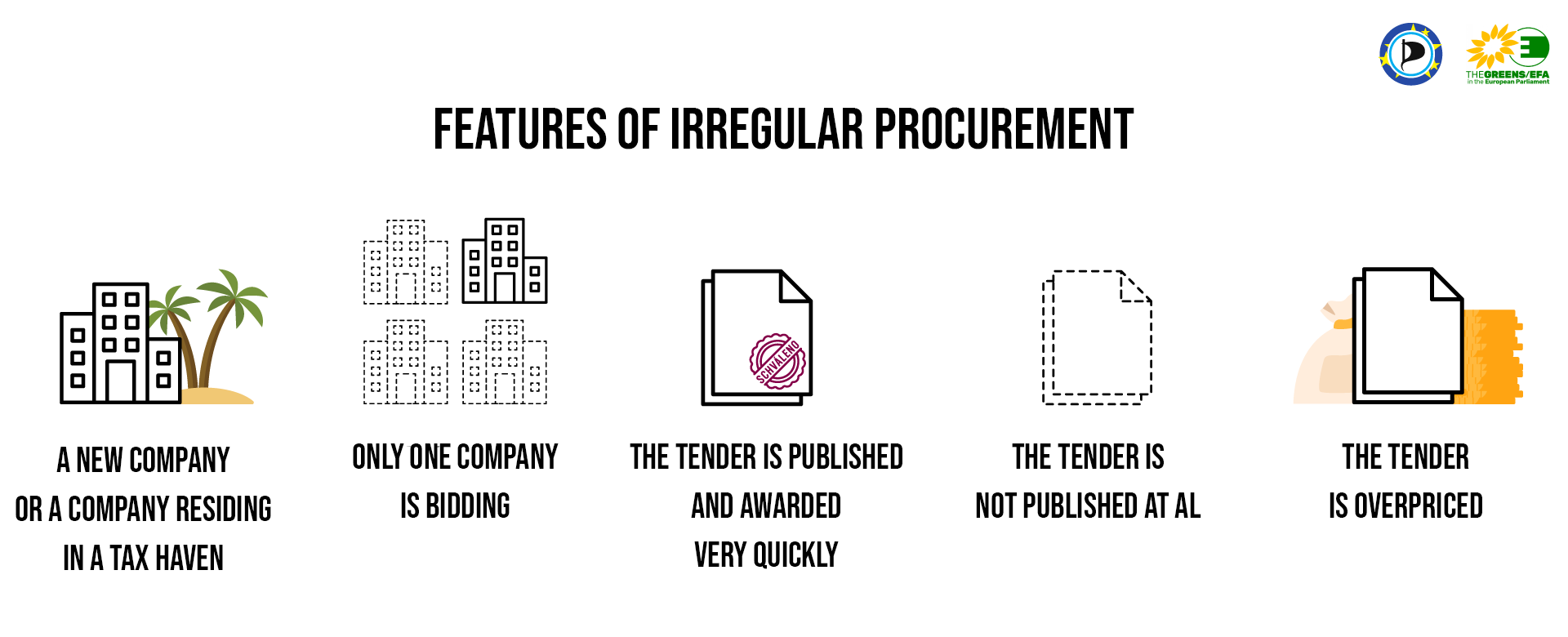

Features of irregular procurement: A new company or a company residing in a tax haven. Only one company is bidding. The tender is published and awarded very quickly. The tender is not published at all. The tender is overpriced

Make a clear and transparent system? Yes, we can!

The lack of transparency in handling public funds is a huge problem, and the EU has not fully succeeded in tackling it. The data on who receives European funding is spread over more than 300 regional, national, and interregional registers, only for the Regional Development Funds. It is difficult to find out who the real owners of companies are – they like to hide behind obscure tangles of small and even smaller companies, which cover their identities. Due to that, the Commission often doesn’t even know where their money ends up.

And what is worse: the data we do have is usually inconsistent, with entire chunks that are missing or unreadable. Countries like Hungary, for instance, carefully register their procurement and subsidy claims, but with so little information that the data is of no use in the end. The loan documentation between Andrej Babiš’s companies was similar: the investigace.cz server showed that the loan contract contains errors and leaves out crucial information.

It is also incredibly challenging to recover the data from public registers only a few years after the transactions. The newly reformed Common Agricultural Policy states that data must be publicly accessible for at least two years, while the EU anti-money-laundering directive asks for five. Czech authorities, for example, such as the Babiš-controlled State Agricultural Intervention Fund, delete all data irrevocably right after the end of the minimum time limit.

How to address this? It’s much easier than you might think.

We need to establish a single EU database of projects that rely on public funding and a register of beneficial owners. In the European Parliament, I have been promoting the creation of such a system within two years. It should also include data on transactions and owners to be entered as part of a standardized scheme. The database is naturally supposed to be fully transparent and based on open-source principles. The data must be publicly accessible for at least ten years – fraud and corruption are not always uncovered right away. We need to make sure that such a system is accessible not only to Member State authorities but also to journalists and the public. A standardized system could also use other Commission tools or, for example, artificial intelligence, to recognize fraud.

Strengthening conflict of interests laws. Creating a digitalized ownership register. Standardized monitoring system. Ensuring compliance with anti-corruption strategies.

What’s next?

Last but not least, we need to ensure compliance with EU anti-corruption directive standards and improve those that don’t work. At the moment, not every state has to comply, so many don’t give a fig about them. Only 14 out of 27 Member States have developed their National Anti-Corruption Strategy – the Czech Republic has not even presented theirs to the Commission yet. This often makes international collaboration between states inefficient, and prosecuting corruption gets a bit harder once more. We do have a lot of tools that could make this better, though!

For instance, the EU has EDES (Early Detection and Exclusion System) for mapping EU subsidy fraud, which has remained almost entirely unused. However, it is a handy system that generates a blacklist of companies that unfairly used the EU budget. Had Agrofert been put on this list a few years earlier (OLAF, the European Anti-Fraud Office, proved Stork’s Nest was a case of fraud a long time ago), we would not have come to a state when it gets hundreds of millions of euros every year.

The new European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO) led by Romanian judge and anti-corruption champion Laura Kövesi could play an equally significant role. The EPPO collaborated with other bodies on investigating and prosecuting offences against the EU budget, and it might prove very useful in the future. If it proves that the offence is mass tax evasion, it has the right to prosecute and fight it.

Andrej Babiš has a lot to explain to us all. He fought to the last drop of blood and at the cost of destroying the good name of the Czech Republic for his right to rob Czech and European citizens alike. However, this year’s election in the Czech Republic ended, one thing is clear: If we really want a new future for our country, we need to make sure it is not torn apart by European oligarchs before our very eyes.

0 comments on “Mr Babiš’s 400 mill CZK in France and how to prevent this from happening again”