Mikuláš Peksa:

The last year brought us one step closer to tax justice. But last year’s success will not take us to our goal without a fundamental transformation.

Euro 2020, the NBA or Squid Game may fill the charts of Google Trends for 2021(https://trends.google.com/trends/yis/2021/GLOBAL/), but the last year was marked by many other important topics in the European Parliament – although I will not deny that I would sometimes rather discuss the hidden meanings of the Korean survival game with my colleagues. In any case, I am glad that we have had the opportunity to address real issues that are important to the European public. The results are worth it.

So we will be talking here about money, or rather about taxes. The word ‘taxes’ is not exactly sexy, but without meaningful collection of funds, a state could hardly function – and for my work in the CONT (Budgetary Control) and FISC (Fiscal Affairs) Committees, this topic is, without exaggeration, a daily bread and butter.

Digitalisation, decentralisation = the future

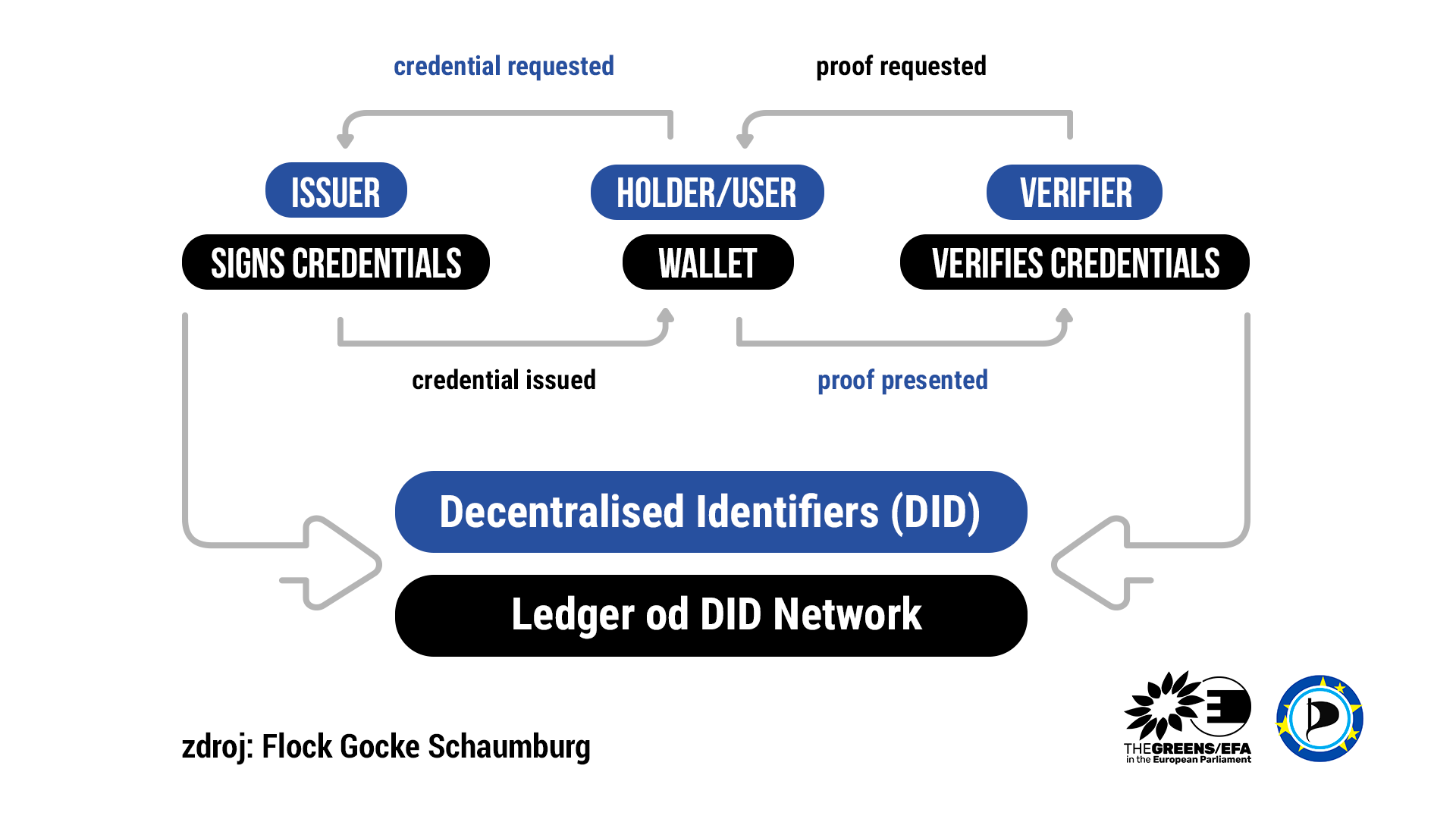

Although “taxes” do not inspire enthusiasm, the field of tax policy is now awash with changes and new approaches – especially when combined with terms such as “blockchain” or “crypto”. The challenge for European legislation is not only to ensure that tax collection is fair and that big players do not avoid paying taxes, but also to create an environment that encourages innovation and more efficient administration. This consideration has led, for example, to the creation of the innovation hub (https://b-hub.eu/), which is supported by European funding and facilitates the development of new crypto-technologies through the sharing of know-how and a less stringent legislative framework.

What could be the outcome? For example, easier verification of contracts and tax documents, more security for medical records and other things that save taxpayers’ time and money – all this of course digitally, in a decentralised way, without the need for a central repository. If you would like to hear more, I recommend a recording (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/public-hearing-on-the-impact-of-new-tech/product-details/20211104CHE09661) of our committee meeting last year, where we talked with experts on digitalisation and tax systems about how the European Parliament and other institutions can meet technological progress.

Focus on the giants

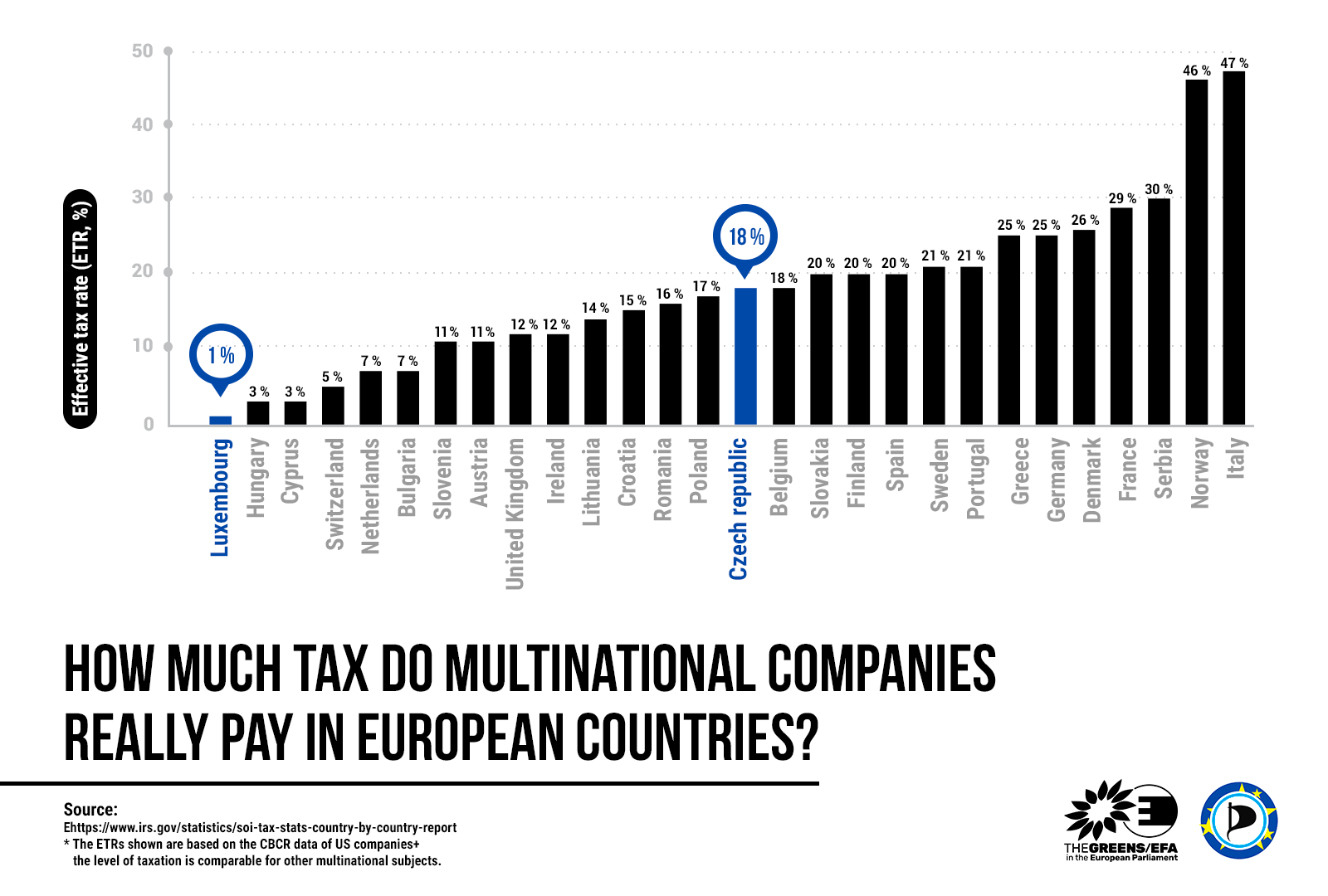

As interesting and necessary as it may be to address the blockchain innovation, in tax matters it is nevertheless still in its infancy. The most significant developments last year, however, were in the area of taxation and transparency of so-called MNEs – large multinational enterprises. The changes, which my colleagues in the EP and I actively participated in (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-9-2021-04-28-INT-3-127-0000_EN.html), were even so ground-breaking that the UK think-tank Tax Justice Network – which, among other things, monitors (https://taxjustice.net/country-profiles/) the volume of tax evasion for each country – identified (https://taxjustice.net/2021/12/20/a-year-the-tide-turned-in-the-fight-for-tax-justice/) 2021 as the year when the “tide has risen” in the fight for tax justice.

And what specifically has changed? Quite a lot. After many years, despite the reluctance of the Babiš’s government, we managed to push through the so-called public Country-by-Country Reporting. With November’s approval in the European Parliament, the pCBCR finally got the green light, and Member States will now have until mid-2023 at the latest to approve legislation requiring large, globally operating corporations to publicly report their earnings, costs, links to other companies and other data on a country-by-country basis. I am glad that our pressure has also helped; transparency by these colossuses is necessary.

The European Commission has also decided (https://www.politico.eu/article/european-parliament-shell-companies/) to crack down on shell companies, which do not engage in any economic activity but merely serve as white horses for other persons and companies. If the proposal is successfully pushed through in 2022, such companies would lose all tax benefits and would have to be listed in a Europe-wide register, which would make the work of tax authorities from all member states much easier. Simpler, quicker and, above all, more effective communication between national institutions is crucial, not least for the fight against tax evasion, so the Unshell initiative is certainly welcome. From the Czech point of view, it is clearly a step in the right direction, because according to recent information, these shell companies registered in Cyprus or elsewhere have been abused by quite a few Czech politicians.

But the most important thing is something else: the approval of a global minimum corporate tax, which was finally approved by the OECD working group in October. I described (https://mikulas-peksa.eu/danove-raje-cesko/) the extent of the problem of the global “race to the bottom” in corporate tax rates back in 2020 – and we even devoted an entire domain to the topic last year – https://spravedlivedane.cz/.

Fortunately, the new minimum rate will eliminate one of the main problems. The multinational companies with a turnover of over €750 million that are to be subject to the minimum rate will lose the ability to “park” their profits in tax havens – and that’s great news not only because it’s normal to pay taxes (https://mikulas-peksa.eu/openlux-banky-transparentnost-II/), but also because even this relatively low tax could bring up to $150 billion into state budgets (https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/what-is-global-minimum-tax-deal-what-will-it-mean-2021-10-08/).

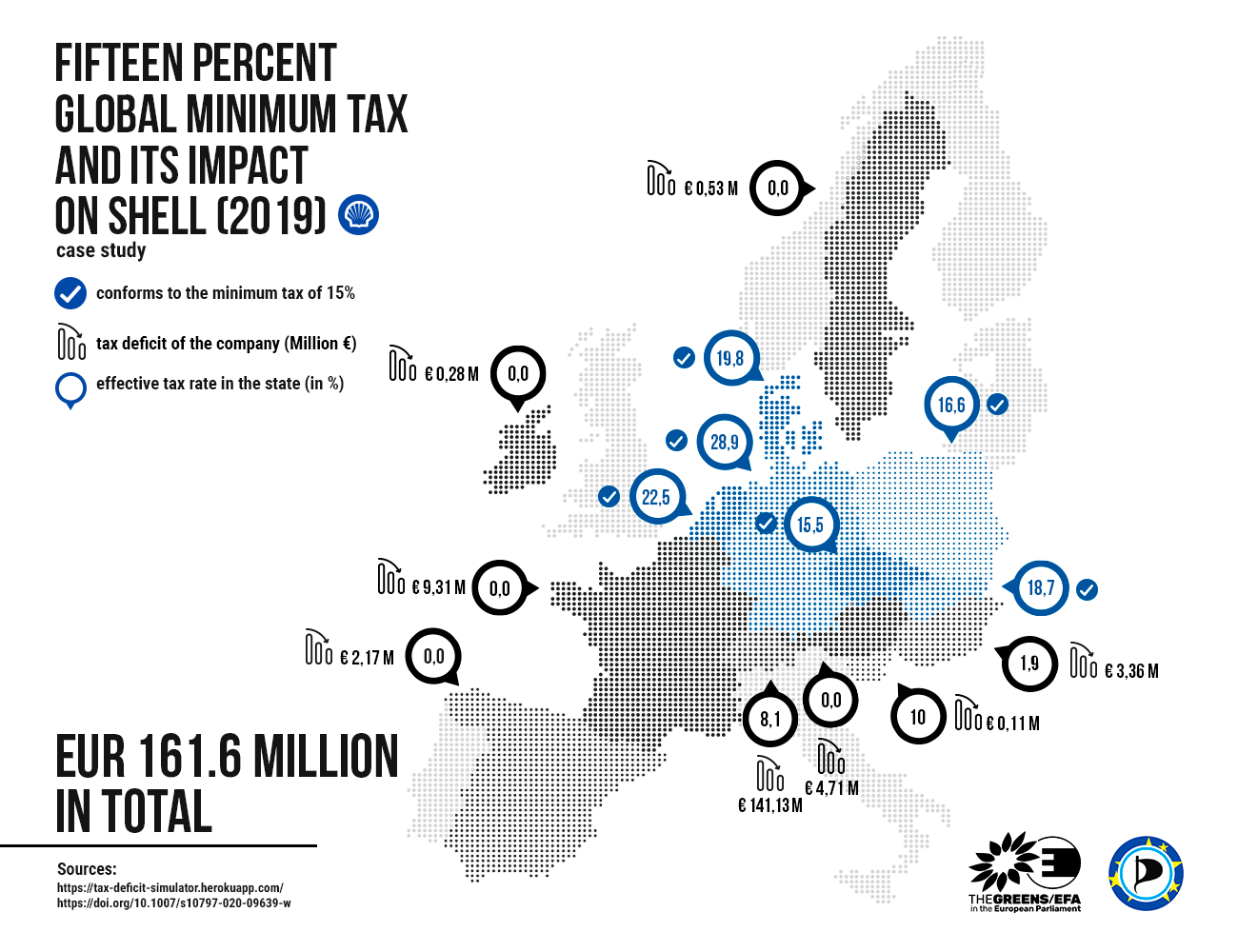

How exactly would this happen? The principle is basically simple: the country where the group’s parent company is based can tax (https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/what-is-global-minimum-tax-deal-what-will-it-mean-2021-10-08/), the rest of the uncollected funds, or require its home company to pay the difference to make up the rate of 15% of their profits. Exactly what this could mean for Shell, for example, a major seller of fossil fuels in countless European countries, is illustrated in the following graphics.

New year, different Europe, same problems

It is important to understand that “approval” does not mean that companies must actually pay the 15% tax to the tax office overnight. As with the pCBCR, governments must first incorporate the approved agreement into their national legal framework. In our country, this difficult task is being tackled first at the European level, so that the application of the minimum tax does not become inconsistent across the single European market – a task that the European Commission is currently in charge of.

However, with a bit of luck, this could happen relatively quickly, as there has been a significant change in Europe’s top institutions since last year: the proposal will be discussed under the French Presidency. And the Elysée Palace, with the upcoming presidential elections in its sights, has a strong interest in showing that Paris still has a strong voice in Europe. Thus, according to President Emmanuel Macron, concrete texts should be ready in the spring of 2022 (https://www.reuters.com/business/eu-draft-texts-implementing-global-corporate-minimum-tax-deal-by-spring-macron-2021-12-09/).

So far, I may have presented a rather hopeful scenery into which 2021 has brought us successfully. However, I will end off on somewhat sceptical note. The problems of the EU’s functioning are coming back to us, or rather to the French presidency, again and again like a boomerang. Europe decides on tax matters on the basis of the principle of unanimity – that is, all Member States must agree on changes to the Council of the European Union*. Thus, we are seeing the same situation as last summer, when countries benefiting from the current dismal state of affairs (typically tax havens and countries with very low rates, such as Luxembourg, the Netherlands or Hungary) threatened to veto the agreement, leading to a “dilution” of the content of the proposal. This is what happened when the OECD agreement itself was being approved – i.e. the text that the European Commission is now “rewriting” into European legislation – after all (https://taxjustice.net/press/oecd-tax-deal-fails-to-deliver/). The same scenario might happen now, in the EU Council.

*Namely in its ECOFIN configuration, and in order for the proposal to be approved, it must be endorsed by the finance ministers of the Member States in the EU Council as well as by the European Parliament..

Naturally, such an outcome would be disappointing for all those who have been campaigning for greater tax fairness in the recent years. Colleagues in my home Greens/EFA group in the European Parliament, with whom I have often worked on international tax in recent years, are of the view that if the European tax havens succeed in eviscerating the minimum tax proposal, then “the more ambitious member states should deepen their cooperation and move forward together” (https://www.greens-efa.eu/opinions/2021/12/17/big-profits-should-mean-fair-taxes/). And I sincerely hope that if this happens, the Czech Republic will be one of these states.

But you can bet that the changes in the tax system do not end with the introduction of the global minimum tax – and they should not. There are so many problems with the way we collect and manage public funds that it would be sad to settle for a few, albeit significant, changes.

0 comments on “The next decade will mark a revolution in taxation. Blockchain is changing the game, but Europe is standing still”